In the 1980s and 1990s, in New York, David Ruggerio was one of the rising stars of French cuisine. Top chef ahead of time, he had everything going for him, the TV courted him, his books were torn out. But this success hid a double life: he was also an active member of the mafia. Decades after his disgrace and his mysterious disappearance from the world of gastronomy, Ruggerio opens up.

In the 90s, David Ruggerio, 30, was at the head of the best French restaurants in New York: La Caravelle, Maxim’s, and Le Chantilly. Little guy from Brooklyn, former boxer turned chef, he now cooks for ex and future presidents (Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump), Wall Street giants (Stephen Schwarzman, Lloyd Blankfein and Jamie Dimon), media moguls (Michael Bloomberg and Martha Stewart), Hollywood princesses (Sophia Loren) and even real princes (Prince Albert of Monaco). New York Times food critic Bryan Miller twice awarded three stars to its restaurants. Gael Greene of New York magazine calls his cooking at Chantilly a “miracle on 57th Street.” He has his own documentary series on PBS, Little Italy With David Ruggerio, and the Food Network gives him a prime-time show, Ruggerio to Go. I mean? – the horizon seems ideally clear and the future bright.

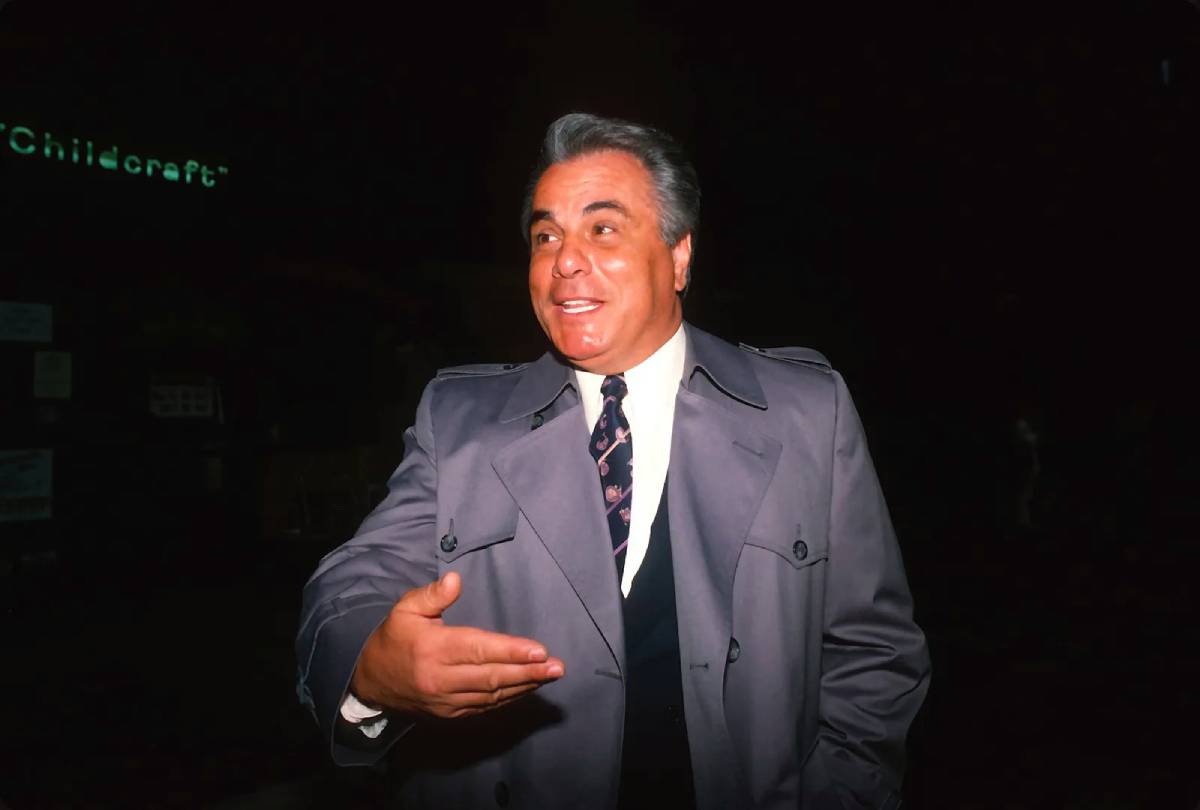

However, everything will collapse in the afternoon of Thursday, July 2, 1998, when the police raid his restaurant, Chantilly. The Manhattan district attorney accuses Ruggerio of defrauding a credit card company of $190,000 by inflating tips left by his customers. At first, Ruggerio denies everything. But facing the threat of a 15-year prison sentence, ends up pleading guilty to attempted robbery in exchange for a five-year probation and a $100,000 restitution deal. Within months, the Food Network canceled his show, his restaurants closed, and he declared personal bankruptcy. Before disappearing body and many from the world of gastronomy. “Overnight, it was all over,” recalls David Ruggerio, while sautéing a few onions in the cluttered kitchen of the modest home he now occupies, at the end of a cul-de-sac in Long Island. We are in 2021, on a beautiful autumn afternoon. At 59, cut like a mirrored wardrobe, with paws like beaters, he seems almost too big in this cramped room. Goat cheese terrine, lobster mignon, grilled chicken and crème brûlée: the menu he prepares is not lacking in panache. Not far from the lunch table, a laptop is open on a small console. This is where Ruggerio wrote his memoirs, but the story of his rise to the upper echelons of New York catering also lifts the veil on his best-kept secret: for decades, alongside his brilliant career as a chef, he was an active member of the mafia, more precisely of the Gambino family. “I was leading a double life,” he sums up soberly.

In the spring of 2021, friends introduced me to Ruggerio, explaining that he was ready to talk about his years in the mafia. Somewhere between Scorsese and Top Chef, his rise and then his spectacular fall constitute one of the most incredible professional trajectories I have ever heard. Over the following summer and fall, I was therefore able to interview Ruggerio about his life as a boss and criminal – it was the first time he had spoken to a reporter about his time in the underworld.

Cosa Nostra and French cuisine

David Ruggerio’s name is an invention. According to his birth certificate, little Sabatino Antonino Gambino was born on June 26, 1962. His Sicilian father, Saverio Erasmo Gambino, was the cousin of Carlo Gambino, the infamous “godfather of godfathers”, who ruled the five major mafia families. from New York in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1980s, Ruggerio hooked up with a Brooklyn gang, led by Gambino capo Daniel Marino. His resume in the mafia? Heroin trafficking, truck hijacking, loan sharking, underground betting, extortion, and participation in several settling of scores. Even in his restaurants, the most lucrative contracts go to suppliers linked to the mafia, he also bribes union officials to ensure that no union comes to poke his nose in his kitchens.

Today, eaten away by guilt and the feeling of having been betrayed, he has decided to break the omertà. In 2014, her 27-year-old son, an aspiring gangster, died of an overdose. If Ruggerio feels responsible, he also says he is deeply hurt and angry that Marino did not show up at the funeral: “When I understood that Danny would not come, I said to myself: “Fuck it. I quit.” »

During our conversations, Ruggerio goes from the hushed register of haute cuisine to the incredibly violent register of the street. Because he has distinguished himself in one as in the other. What he is going to tell me offers a unique point of view on New York at the end of the 20th century, a period which corresponds both to the end of the unchallenged reign of French cuisine in New York and to the decline of mafia in the city – a time when the New York Times described the Caravelle as an “elegant temple of French gastronomy in Midtown” and when the feds were dismantling the city’s mafia families one by one. A time, too, when not everyone had a camera in their pocket. New Yorkers of the rich and famous could flaunt themselves in public: what happened in the fancy restaurants stayed in the fancy restaurants. And those of Ruggerio have been the scene of totally crazy episodes.

In the author’s note of his unpublished memoirs, one can read: “Everything in these pages is rigorously accurate….. There was no need to add more, the facts were already horrifying enough.” I wondered if he was exaggerating for a little dramatic effect, as wise men are known to do. I cross-checked everything, names, press articles, public archives, court records and personal photographs from the time. I also spoke to former FBI agents and former Ruggerio employees, who confirmed mobsters frequently hang around his restaurants. Bruce Mouw, who ran the FBI’s Gambino Division in the 1980s and 1990s, confirmed that Le Chantilly was one of Danny Marino’s haunts: “We knew. Mouw’s successor in the Gambino Division, Phil Scala, confirmed that Ruggerio was a member of Marino’s team: “Danny was bragging about Ruggerio’s talents and inviting all his friends to his restaurants. »

“When you called about David, I thought it was the FBI at first,” Dawn DuBois, a former corporate lawyer who worked at Chantilly, tells me. “I remember one time when we owed money to a meat producer. A guy stormed into the restaurant brandishing a baseball bat and said, “You better pay, or next time I’ll use it.” Me, I’m just a nice girl from Brooklyn, I thought, “What’s going on here?” »

During our exchanges, Ruggerio was candid, sometimes quite shockingly. But members of organized crime are – unsurprisingly – also organized in what they admit and what they don’t admit. In detailing his double life, Ruggerio openly spoke about the brutal crimes committed alongside now-deceased mobsters. He was, however, much less talkative when I asked him about his more recent activities. Ruggerio was adamant that while he quit the mafia, he doesn’t want to cause any harm to active members of the Gambino family. “I’m not here to cooperate, against anyone. That’s not why I did this,” he told me. Over lunch, I asked him if he was afraid that by making his business public, he would become a target for the mafia. ” We’ll see. When I lost my son, I knew it was all over for me. »

Blood relationship

His childhood in Brooklyn could come right out of a Dickens novel. Before his birth in June 1962, outside the bonds of marriage, his father Saverio, a heroin trafficker, was expelled from Brooklyn, heading to Sicily where he was imprisoned in the infamous Ucciardone penitentiary in Palermo. At four years old, Ruggerio says he discovered the lifeless body of his little sister in her crib. “His coffin was so small that we didn’t need a hearse. “A year later, his pregnant mother, bedridden, died of an asthma attack: “The last memory I have of her is her inert body transported out of the house. »

After his father was imprisoned, his mother had married one of his friends, who agreed to adopt the kid, but demanded that he change his first and last name. “He beat me at the slightest opportunity,” says Ruggerio. He inherits a new first name, David, inspired by his mother’s favorite film, David and Lisa, released in 1962, a love story in a psychiatric hospital (his sister’s name is Lisa). He hates his adoptive father’s last name and changes it as soon as possible; it will be Ruggerio, the Americanized spelling of his grandmother’s maiden name, Ruggiero.

When his mother dies, their adoptive father sends David and Lisa to live with their maternal grandparents in Park Slope, a Brooklyn neighborhood. They later move to East Flatbush, a middle-class enclave where Barbra Streisand and Rudy Giuliani grew up a generation before. “My mother’s family was straight as justice,” Ruggerio recalls. But in the 1960s, East Flatbush became one of the toughest neighborhoods in the city. “It was a different time in Brooklyn. Murders were commonplace. Young David finds refuge in his grandmother’s kitchen, a veritable oasis. “I loved watching her make pasta by hand, knead bread or just canned vegetables. Everything she did, she did with care and precision. »

The sad reality quickly catches up with him. Shortly after the move, his grandfather had a heart attack; again, it is the young man who discovers the body, in the bathtub. According to Ruggerio, his early experiences with death stripped him of his ability to empathize. “I learned very early on that I had a very cold side in me. This harshness is also a means of survival. From primary school, he embarked on his first scams: from hats, he went on to steal Christmas trees, fireworks or jeans, which he sold to local thugs. He honed his brawling skills at a local gym run by famed Jewish boxer Izzy Zerling. It was at this time that he was arrested for the first time, the beginning of a long series of arrests for gambling or assault. “Did I want to become a gangster? No, I never said to myself: “I want to be a gangster when I grow up”. All I wanted was to survive until tomorrow. »

Ruggerio then began dating one of his father’s lieutenants, Egidio “Ernie Boy” Onorato: “Ernie was younger than my father and must not have weighed more than 65 kg, but he was the most ruthless gangster I had ever seen. have never seen. Onorato died in 1998, allowing Ruggerio to speak freely of his mentor today. One night, when he was 11, he accompanied 23-year-old Onorato to a bar on the Lower East Side. He waits on the street as his eldest enters and lures a federal informant, named Anthony Finn, into an alley. Onorato beats Finn up before shooting him in the back of the neck and stuffing a bag of coke in his mouth. “We loaded the body into a car and drove it to the corner of A and Ninth Avenue. Onorato and Ruggerio have never been officially linked to the crime.

In 1976, when Ruggerio was 13, his father was released from prison and returned to Brooklyn. Davis dreads the moment when he will have to explain to his father that he gave up the Gambino name. “When I told him my name, he just said, ’We’ll take care of it.’ He never called me David. Always Sabatino. When Father Saverio opens a fish market and garage in Mill Basin, Brooklyn, he puts Ruggerio to work. “He used to wear things out in his garage, and smuggle heroin through the fish market. They brought sardines, squid and frozen octopus in boxes. The fish were stuffed with pure heroin. When she landed here, the dogs couldn’t smell her. »

Ruggerio works at another of his father’s front companies: a dog grooming salon. To make ends meet, he traffics in exotic animals in the back room. One Christmas, Frank Piccolo, a Gambino capo also known as Frank Lanza, buys a monkey named Bongo for his grandchildren. But very quickly, Piccolo demands that David take him back. “I let this little motherfucker out of his cage, and now all he does is sit in the corner, shit, and throw his shit at me!” barks an irate Piccolo into the phone. With a friend, the future top chef picks up the monkey and, late at night, releases it in the Prospect Park Zoo.

In the summer of 1977, as Ruggerio was about to enter high school, his father took him to Sicily to be initiated there. It is Santo Inzerillo, the brother of Totuccio Inzerillo, the boss of Palermo, who presides over the ceremony in the basement of a café in Castellammare del Golfo, the ancestral village of his family. Armed with a needle of questionable cleanliness, a man tattoos a burning cross on the right shoulder of the young mobster. Accompanied by the words Uomo de Fiducia (“trustworthy man”).

Shortly after their return to Brooklyn, Saverio was arrested and again deported to an Italian prison. Before leaving, he instructs Onorato to watch over David. At that time, Ruggerio was already involved in Ernie’s excesses of violence. In March 1978, he helped the latter torture and kill a 56-year-old Genovese and Colombo associate, Pasquale “Paddy Mac” Macchirole, before leaving his body in a car trunk in Brooklyn. Onorato generously rewards his colt. “Ernie had a house in Fort Lauderdale. In the middle of the living room, in the basement, was a large coffee table. There was always a quarter or half a kilo of coke on it. Ernie received girls, everyone was naked. At 14, 15, I already knew a lot about sex. Ruggerio estimates that he amassed around $50,000 in his teenage years from the drug trade – or $230,000 today – which he hid in the attic at his grandmother’s house. “At 16, I was able to send my grandmother and my sister on a tour of Italy for a month. »

Crimes and Chantilly

Greyed out, it won’t stay that way for long. During the summer of 1980, his friends began to die around him. The first will be an aspiring stand-up comedian, 22-year-old Joey “Skeetch” Cannizzaro. “Skeetch dreamed of being in it. He wanted to be a gangster at all costs,” says Ruggerio. One evening, when he goes to Onorato’s, he notices that Cannizzaro is limping. “He tells me that he fell in love with a Jewish girl, and that she forced him to be circumcised. He shows me a gold chain around his neck, with a kind of pendant that looked like dried chicken skin: it was his foreskin. I said, ’Get rid of the fucking thing! And above all, above all, do not speak to Ernie about it.” »

They then go to an old building in East New York, Onorato has sent Cannizzaro to get some Chinese food. “Everyone is picking up boxes from the table. Skeetch leans over, and his goddamn gold chain falls off. And Ernie goes, “Oh! What is that thing ?” And there, I hear Skeetch launch into the story of his circumcision! Frightened, I look at Ernie: his face is completely expressionless, impassive. Against the back of a chair, I notice a lead pipe. Ernie picks it up, and there he unpins complete. He goes after the kid until his face is reduced to mush. Then he turns to me, and I thought: I’m next. He places the pipe a few centimeters from my face. He is dripping with blood. He said to me: “You are the one who brought us this idiot! That’s your fucking problem.” We rolled Skeetch’s body in an old rug. And then I heard him moan. He was still alive. Nevertheless, they weighed down the body of the unfortunate man with lead window frames before throwing him into the waters near Sheepshead Bay.

In July 1981, it was the turn of Ruggerio’s best friend, Caesar Juliani, a 21-year-old bodybuilder, to be found dead, shot in the head, behind the wheel of a parked car in Brooklyn. According to David, Onorato would have eliminated him on the orders of a mobster from the Bronx whose girlfriend was fooling around with him.

Shortly after Juliani’s murder, his girlfriend overdoses and drowns at Jones Beach, Long Island. According to friends of Ruggerio, she took pills that Onorato gave her. He thinks Onorato gave him pure heroin because he was furious with the time David was spending with her. “That’s when I decided I was going to kill him,” Ruggerio says. He plans to kidnap his mentor and murder him in the back of a stolen ice cream truck.

But before he can put his plan into action, a Gambino henchman, Peter “Little Pete” Tambone, intervenes. “Little Pete must have been about 6 feet tall. He said to me, ’I know that guy Ernie is with your dad, but let’s be honest, he’s U gira diment’ – a Sicilian term that basically means ’gone crazy’ . Then: “You’re going to kill him and go to jail, or he’s going to kill you, or you’re both going to die.” Friday, come to Grotta D’Oro. »

Good fillet

Grotta D’Oro was a popular Italian restaurant in Sheepshead Bay. On Friday evening, Gambino capo Carmine Lombardozzi was doing business there from his Rolls-Royce, parked just outside. Specializing in “pump and dump” stock market fraud and loan sharking, Lombardozzi was perhaps the one who brought in the most money for the Gambino family. He was called the King of Wall Street. When Ruggerio arrives, Little Pete waves him over. Lombardozzi whispers to him that he will now work for him. The message is clear: Ruggerio can’t touch Ernie Onorato, but Onorato can’t touch him either. “Carmine was the 900-pound gorilla that Ernie was definitely not going to mess with. As of that day, I was one of the Carmine guys. »

New affiliation, but also new constraint: Lombardozzi expects his men to find real jobs to divert the attention of the police. Ruggerio’s outlook is bleak – he was kicked out of high school and has a criminal record. He nevertheless has a secret passion: cooking. If it is necessary to work, it will be chief.

Despite his heritage, Ruggerio has no desire to work in an Italian kitchen. “Italian restaurants at the time were pathetic. Red sauce everywhere. Pizza by the mile. In the early 1980s, French cuisine dominated the New York gastronomic scene, which is what interested David. “I bought all the French cookbooks by Julia Child, Auguste Escoffier and Jacques Pépin. I started to memorize French terms. I was reading the New York Times food section, Jay Jacobs restaurant reviews in back issues of Gourmet. I knew all the best restaurants. »

Among these, La Caravelle. With a menu that has remained virtually unchanged since it opened in 1960. Classics: pike dumplings, sea bass à la Dugléré and snow-covered eggs. “Walking in, I felt like I was in a movie,” Ruggerio recalls. The kitchen was in the basement of the Shoreham Hotel. There were all those Frenchmen in immaculate white hats running around. No one spoke English. One day, after the lunch service, the young mafia approached the boss, Roger Fessaguet. “Before I could say three words, he barked, ’We’re not hiring! Get out !” I knew right away that this is where I wanted to work. »

French cuisine is like the mafia

Spring 1981: La Caravelle hires Ruggerio as an entremétier, a beginner cook who works mainly on vegetables and soups. He must absorb a staggering amount of information at a breakneck pace, in a language he barely understands. The chefs shout at him an order of Tosca Consommé and another of Green Meadow Consommé, and he immediately has to tell the difference between one (chicken consommé thickened with tapioca and topped with julienned carrots and chicken dumplings, truffles and foie gras) and the other (chicken broth garnished with finely cut vegetables and fresh sorrel). He keeps the classic Le Répertoire de la Cuisine at his post, and flips through it feverishly as soon as it is lost, that is to say often. “The first two serves were absolute hell. They yelled at me all the time.

Ruggerio quickly understands that French cuisine is not so different from La Cosa Nostra. Both are governed by rigid hierarchies and old-fashioned codes. “At La Caravelle, they inspected your drawer twice a day, and if your knives weren’t clean and sharp, they threw everything on the floor,” says Ruggerio. He respects the way the owner, Robert Meyzen, enforces the dress code of the dining room with an iron fist. “Once he wouldn’t let Jackie Kennedy in because she was wearing pants. Another time, Ralph Lauren arrived with a cowboy bolo tie. Meyzen told him that the tie was compulsory. Ralph replied, “I have one there.” Meyzen said: “No, that’s good for the horses!” And he kicked him out. »

When Ruggerio is not in the kitchen, he plays the bosses in the street. He compartmentalizes his two lives. At La Caravelle, no one knows. “He was simply talking about his childhood in Brooklyn and his past as a boxer,” recalls Fabrizzio Salerni, former La Caravelle, who now works for Daniel Boulud.

However, it is difficult to escape the violence. It will almost cost him his new career. One night, a few months after landing the job at La Caravelle, Ruggerio was attacked on the Brooklyn subway. In the struggle, Ruggerio grabs his attacker’s knife and stabs him in the arm and stomach. He invokes self-defense, but the Brooklyn prosecutor, discovering his criminal record, sticks him with an attempted murder. He spent ten days at Rikers Island until Danny Marino, Lombardozzi’s nephew, bailed him out. Marino orders him to leave town.

Ruggerio returns to La Caravelle and begs Fessaguet to find him a position in France. The French sent him to the Côte d’Azur to follow the training of the famous chef Jacques Maximin, the “Bonaparte des fourneaux”, at the Chantecler – two Michelin stars – the restaurant of the Negresco in Nice. After a year, Maximin pushed Ruggerio to finish his apprenticeship with some of the best French chefs: Roger Vergé, Maximin’s mentor, Boulud, then Alain Ducasse, in his three-star Michelin restaurant, Le Moulin de Mougins, near of Cannes. He then moved to Michel Guérard, a pioneer of new cuisine in his restaurant in the Pyrenees. Finally, he makes a passage in the legendary restaurant of Paul Bocuse, the Auberge du Pont de Collonges, in the suburbs of Lyon.

Meanwhile, Lombardozzi’s team deals with their legal issues. “The guys visited my abuser at his mother’s home in Brooklyn, and convinced him not to cooperate with the investigation,” Ruggerio said. “Let’s say they spoke to him the language that this guy understood. »

“Gotti loved Maxim’s”

In the fall of 1983, Ruggerio returned to New York. La Caravelle took him over as a saucier, a position one step below sous-chef. He was then only 21 years old. Why didn’t he quit the mafia when his restaurant career was booming? “I had a terrible need to be wanted and respected. And I never really felt like I belonged in the world of gastronomy. It was in the street that I felt respected. »

Ruggerio’s job caught the eye of rising Gambino figure Danny Marino. “Danny loved good food. Never jogging, never jewelry. His thing was nice costumes and great restaurants,” says David.

When Ruggerio returns to La Caravelle, the wind of new cuisine blows through New York’s French restaurants. This trend toward lighter, more inventive cuisine is creating opportunities for young American chefs. In 1984, Michael Romano, 32, replaced Fessaguet at La Caravelle and appointed Ruggerio sous-chef. A few years later, Danny Meyer poached Romano to supervise the kitchen of the Union Square Café: at 26, Ruggerio became the executive chef of La Caravelle.

The Gambino family, too, is in the midst of a revolution. Nine days before Christmas 1985, Castellano was shot dead in Manhattan. John Gotti ordered the murder. ” I’ll never forget. I was at La Caravelle. I got the call and rushed to the scene. There were cops and photographers everywhere,” Ruggerio recalls. Gotti’s coup puts him in danger, since he is close to Marino, a Castellano faithful. But his place in the restaurant business will protect him from the ire of Gotti – he wants to meet him: “What you have to understand is that when the Mafiosos get together, what they talk about first is is what they ate the night before or lunch. Most of the time, they talk about food. »

In April 1990, Pierre Cardin hired Ruggerio to reinvent his Maxim’s restaurant in New York. “Gotti loved Maxim’s. The Madison Avenue establishment was a virtual replica of its Parisian counterpart. In October 1990, Gotti asked the young chef to provide catering for his 50th birthday at Maxim’s. “It was a fucking feast.” It will be Gotti’s last birthday as a free man: two months later, he falls for racketeering. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he died of cancer in 2002.

Ruggerio’s notoriety is growing, it becomes more and more difficult to hide his double life. In January 1992, Bryan Miller awarded Maxim’s three stars in The Times. Ruggerio should have eased off his mafia activities at that time. But quite the opposite is happening. “I was tortured. I could tell right from wrong, but sometimes I just couldn’t help myself,” he explains.

During the summer of 1992, restaurateur Camille Dulac courted Ruggerio to take over the kitchen at Chantilly, on East 57th Street, which had been in decline for several years. The young chef is modernizing the menu, injecting Italian influences, crab ravioli or quail risotto. Shortly after, Dulac learns that the Times and New York magazine are preparing to publish (good) reviews.

One afternoon in February 1993, Ruggerio is preparing dinner service when the butler bursts into the kitchen: the police are there and have the locks changed. Ruggerio comes running. A man in a trench coat approaches and introduces himself, he is an auctioneer commissioned to liquidate the restaurant. Chantilly has been bankrupt since 1991; Ruggerio says Dulac hid it from him. “I was beside myself. He wants to find a way to keep the restaurant open until the reviews come out in a few days. A positive review could fill the booking book for months.

At the bottom of the hole

Ruggerio watches the auctioneer, feeling like he’s seen him before. Then it clicked: it was a little mobster from Brooklyn, a certain named Bob Moneypenny. He then leans towards him and whispers in his ear: “I am a friend of Joe Watts. “The guy went livid,” Ruggerio recalled. Gambino member Joe “The German” Watts was one of the city’s most feared mobsters. Moneypenny flatly apologizes and calls the court for permission to put the liquidation on hold. “We opened at 5:30 p.m. as if nothing had happened,” Ruggerio recalls. The following week, The Times and New York magazine published rave reviews. Chantilly has become one of the most popular restaurants in town. Money is flowing.

But the restaurant was still bankrupt. Never mind, with the complicity of Moneypenny, Ruggerio rigs the auction and gets the Chantilly for 100,000 dollars. “The cellar alone contained half a million in wine,” he explains. This takeover revives David’s ambitions. “Everyone was licking me when I became the owner of the establishment. In the spring of 1994, Ruggerio was singularly lacking in common sense when he teamed up again with Dulac to open an Italian restaurant, Nonna. “It was a huge mistake. But the most serious mistake will be to accept a six-figure investment from Marino and thus sit by one of his golden rules: never borrow money from the mafia. “Sheer stupidity and ego on my part,” Ruggerio says. Marino is about to serve six years in prison for complicity in murder. He warns the two partners, if Nonna closes, they will have to reimburse him in full.

The Gambino family, too, is in the midst of a revolution. Nine days before Christmas 1985, Castellano was shot dead in Manhattan. John Gotti ordered the murder. ” I’ll never forget. I was at La Caravelle. I got the call and rushed to the scene. There were cops and photographers everywhere,” Ruggerio recalls. Gotti’s coup puts him in danger, since he is close to Marino, a Castellano faithful. But his place in the restaurant business will protect him from the ire of Gotti – he wants to meet him: “What you have to understand is that when the Mafiosos get together, what they talk about first is is what they ate the night before or lunch. Most of the time, they talk about food. »

In April 1990, Pierre Cardin hired Ruggerio to reinvent his Maxim’s restaurant in New York. “Gotti loved Maxim’s. The Madison Avenue establishment was a virtual replica of its Parisian counterpart. In October 1990, Gotti asked the young chef to provide catering for his 50th birthday at Maxim’s. “It was a fucking feast.” It will be Gotti’s last birthday as a free man: two months later, he falls for racketeering. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he died of cancer in 2002.

Ruggerio’s notoriety is growing, it becomes more and more difficult to hide his double life. In January 1992, Bryan Miller awarded Maxim’s three stars in The Times. Ruggerio should have eased off his mafia activities at that time. But quite the opposite is happening. “I was tortured. I could tell right from wrong, but sometimes I just couldn’t help myself,” he explains.

During the summer of 1992, restaurateur Camille Dulac courted Ruggerio to take over the kitchen at Chantilly, on East 57th Street, which had been in decline for several years. The young chef is modernizing the menu, injecting Italian influences, crab ravioli or quail risotto. Shortly after, Dulac learns that the Times and New York magazine are preparing to publish (good) reviews.

One afternoon in February 1993, Ruggerio is preparing dinner service when the butler bursts into the kitchen: the police are there and have the locks changed. Ruggerio comes running. A man in a trench coat approaches and introduces himself, he is an auctioneer commissioned to liquidate the restaurant. Chantilly has been bankrupt since 1991; Ruggerio says Dulac hid it from him. “I was beside myself. He wants to find a way to keep the restaurant open until the reviews come out in a few days. A positive review could fill the booking book for months.

At the bottom of the hole

Ruggerio watches the auctioneer, feeling like he’s seen him before. Then it clicked: it was a little mobster from Brooklyn, a certain named Bob Moneypenny. He then leans towards him and whispers in his ear: “I am a friend of Joe Watts. “The guy went livid,” Ruggerio recalled. Gambino member Joe “The German” Watts was one of the city’s most feared mobsters. Moneypenny flatly apologizes and calls the court for permission to put the liquidation on hold. “We opened at 5:30 p.m. as if nothing had happened,” Ruggerio recalls. The following week, The Times and New York magazine published rave reviews. Chantilly has become one of the most popular restaurants in town. Money is flowing.

But the restaurant was still bankrupt. Never mind, with the complicity of Moneypenny, Ruggerio rigs the auction and gets the Chantilly for 100,000 dollars. “The cellar alone contained half a million in wine,” he explains. This takeover revives David’s ambitions. “Everyone was licking me when I became the owner of the establishment. In the spring of 1994, Ruggerio was singularly lacking in common sense when he teamed up again with Dulac to open an Italian restaurant, Nonna. “It was a huge mistake. But the most serious mistake will be to accept a six-figure investment from Marino and thus sit by one of his golden rules: never borrow money from the mafia. “Sheer stupidity and ego on my part,” Ruggerio says. Marino is about to serve six years in prison for complicity in murder. He warns the two partners, if Nonna closes, they will have to reimburse him in full.

Author: Michael Zippo

https://linkedin.com/in/michael-zippo-9136441b1

[email protected]

Sources: VanityFair, IO Donna

Written by Michael Zippo

Michael Zippo, passionate Webmaster and Publisher, stands out for his versatility in online dissemination. Through his blog, he explores topics ranging from celebrity net worth to business dynamics, the economy, and developments in IT and programming. His professional presence on LinkedIn - https://www.linkedin.com/in/michael-zippo-9136441b1/ - is a reflection of his dedication to the industry, while managing platforms such as EmergeSocial.NET and theworldtimes.org highlights his expertise in creating informative and timely content. Involved in significant projects such as python.engineering, Michael offers a unique experience in the digital world, inviting the public to explore the many facets online with him.